To mark Black History Month, we spoke to Don John, Race Development Officer for Southampton City Council, who has compiled a fascinating history of Black Stories from Southampton, including several of people with strong Christian faith who were connected to churches in our diocese, two of whom are featured below…

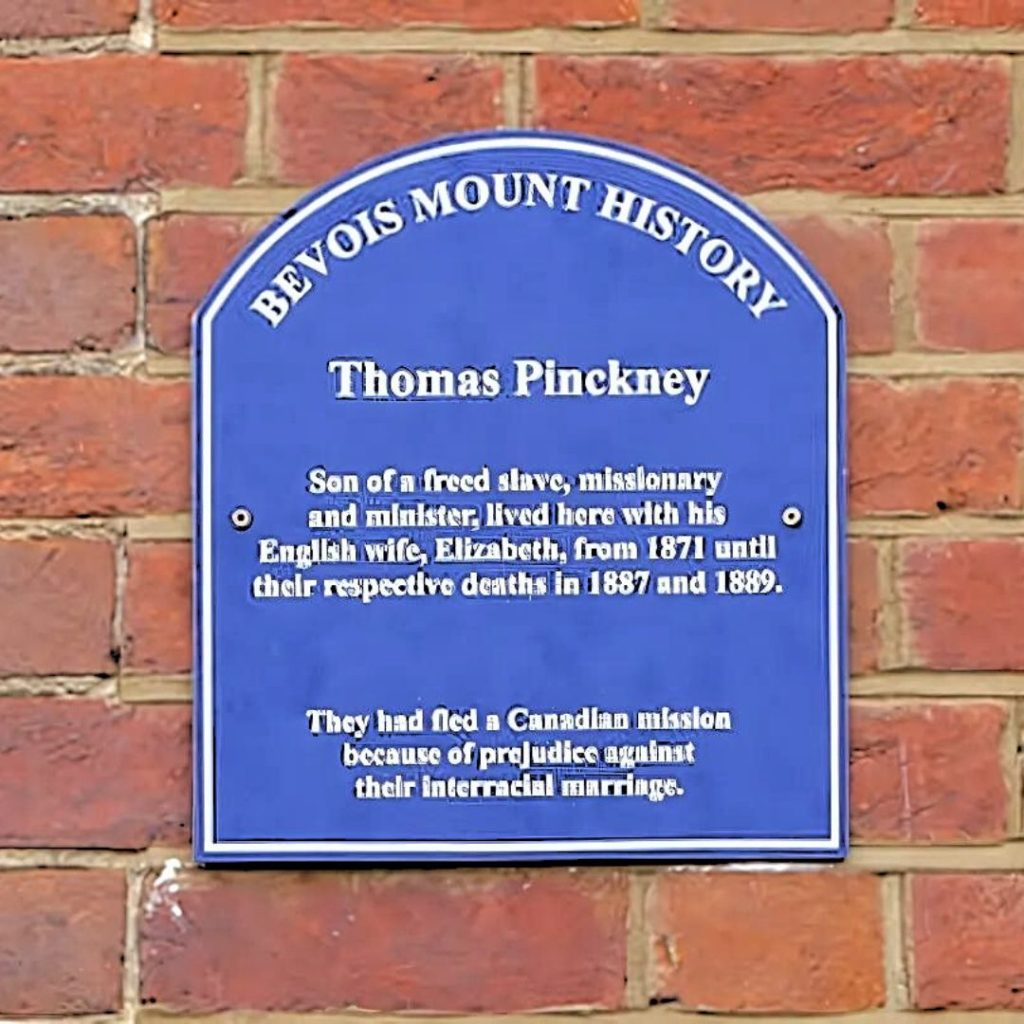

Revd Thomas Pinckney (1809-1887)

The Revd Thomas Pinckney was an Episcopalian clergyman and missionary who lived in our diocese in the late 19th century.

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1809, he is believed to have been the son of a freed slave rather than been born into slavery himself. The surname ‘Pinckney’, however, does have its roots in slavery, as it comes from a politically powerful family of planters in Charleston who owned hundreds of slaves.

It’s likely that Thomas’s education was funded by the Episcopalian Church of America, and it was into this church, in the city of Philadelphia, that he was ordained in 1852. Shortly after his ordination, Revd Thomas set sail for the West African country of Liberia as a missionary. There was a very high mortality rate in this part of the world, due to a harsh climate, prevalent disease, poor housing conditions, and hostility from the indigenous inhabitants of the country. While he persevered with his missionary work in Liberia, Revd Thomas’s health suffered, and after four years, he returned home to the United States.

It was two years later, in 1858, that Revd Thomas travelled to England. We can see from local newspaper reports that he travelled around the country, giving talks on behalf of the Colonial Church and School Society. At the society’s annual meeting in London, William Wilberforce, the Earl of Shaftesbury, described Revd Thomas as “the representative of the much-wronged coloured race”.

It was in London that Revd Thomas obtained a missionary posting to Chatham in Quebec, Canada. In Chatham, Thomas established a school, with learning based on biblical principles, working closely with powerful black abolitionist families. It was also in Canada that he met Elizabeth King, a white English missionary, who he married on 29 February 1860.

Despite Chatham having a diverse society, it was not a particularly tolerant one. Many in the white community were scandalised by interracial marriage, and handbills were issued urging legislation to prevent what was stigmatised as “this violation of the law of God, and our common nature”.

It is likely due to this prejudice that 1870 found Revd Thomas and his new wife back in England. Initially staying for a short period in Freemantle, Southampton, the couple made a permanent home on Avenue Road, Bevois Mount, Southampton, spending the rest of their lives here. They died within two years of each other – Thomas in 1887 and Elizabeth in 1889 – and are both buried in Southampton Old Cemetery.

When it comes to Revd Thomas’s ministry, in the 1871 census, he told the enumerator that he was an “Episcopal Clergyman without cure of souls”. We can’t know the reason that Revd Thomas, while ordained, never worked in a parish setting, but it’s an interesting point to reflect on. Was he not called to parish ministry, or did he encounter prejudice due to his race and background?

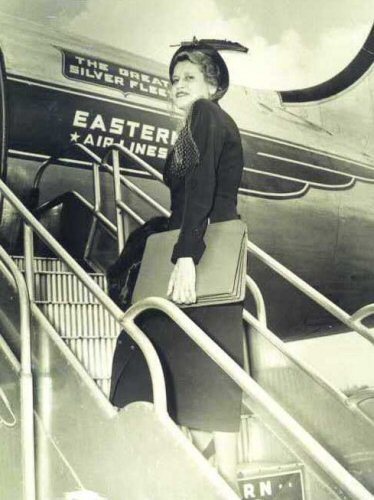

Mae Street Kidd (1904 – 1999)

Mae Street Kid (pictured above) was a woman of strong Christian faith who worked in our diocese at a church in Netley for the American Red Cross during WW2…

Mae was a civic leader and political activist born in 1904 in Kentucky, sitting for seventeen years in the Kentucky General Assembly, where she crusaded energetically for housing rights. At the time of her death, the state’s governor, Paul Patton, said that “Kentucky has lost a pioneer and champion of equal rights for minorities and women”.

During the Second World War, Mae was made assistant director of the American Red Cross service club and travelled to the UK. This club was for black soldiers who were waiting to be shipped across the English Channel to the war front, set up in a converted church near Netley Hospital, the large military hospital in Netley near Southampton.

Black and white soldiers were not allowed to mix in the armed services, so the club was completely segregated. The club was in a converted church building and there were no sleeping facilities, but Mae tried to make things pleasant for the soldiers.

During her time in Southampton, Mae overcame the numerous racist incidents, and when she returned to America, she became a champion of minority and women’s rights. Mae has also been recognised for her work in Southampton – the project ‘Black Plaques Southampton‘ has put up plaque celebrating her work, which can be found at the Royal South Hants Hospital, Southampton.

Mae’s biography, Passing for Black: The Life and Careers of Mae Street Kidd, talks about being born to a white father and black mother and how this meant she didn’t always fit into either the black or white communities. It also talks about her sincere Christian faith and how it motivated her work:

“I believe firmly in God, and my faith has increased as I’ve gotten older. But I have my own special understanding of God. I believe that He is everywhere. He’s like a giant net or a spider web that covers everything and draws all things together. We don’t have to look in special places for Him because He’s with us everywhere now. As a Christian, I believe we can seek a special relationship with Him through His only Son, Jesus Christ. When we die, we become one with Him.”