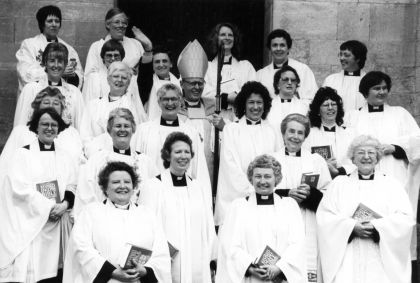

On 12 March 1994, the first 32 women were ordained as Church of England priests at a service at Bristol Cathedral. Thirty years on, we look at the lives of a few of the women who, though never became priests themselves, campaigned throughout the earlier decades of the 20th century to bring the change about.

Dame Betty Ridley

While never feeling called to be ordained herself, Betty Ridley spent half a century quietly campaigning for the ordination of women as priests in the Church of England. Having grown up in the church – her father was rector of Poplar, later becoming Bishop of Stepney, then Bishop of Southwell – it is hardly surprising that in her teens, Betty felt a call to be a missionary. However, her life took a different path when, at the age of 19, she married her father’s chaplain, the Reverend Michael Ridley.

A year later, while staying with her parents at the bishop’s palace in Southwell, she attended a meeting of the Central Council for Women’s Church Work, which her father chaired. Betty informed these formidable ladies that they were wasting their time, and ought to be working for women’s ordination. To their credit, the ladies invited Betty to join them, and in 1930 Betty began her lengthy career on church committees.

When she was widowed at forty-four, Betty directed her full energies toward the central councils of the Church of England, a forum in which she had been moving with increasing confidence. In 1945, she had been elected to the Church Assembly (which became known as the General Synod from 1970) and became vice-president of the British Council of Churches in 1954–6.

Betty also became the first woman on the Central Board of Finance, on which she was to serve for the next 25 years, and the first woman member of CACTM (the Central Advisory Council for Training for the Ministry). In 1954 she was made vice president of the British Council of Churches, and later became chairperson of the influential administrative committee of Free Church moderators and senior churchmen.

In 1959, Betty was made a Crown appointee to the Church Commissioners. She described herself as “one of those tiresome but useful people who are always being put on things to link up with something else”. It wasn’t until 1968, when she was almost 60, that Betty was offered her first salaried post, setting up a department to deal with redundant churches for the Church Commissioners. This led to yet greater responsibility in 1972, when she became the first woman to be appointed as Third Church Estates Commissioner.

Whilst on each of these committees and boards, Betty continued to support the cause of the ordination of women up to the point where, in July 1975, the synod voted that there were “no fundamental objections” to the principle of women priests. But she surprised everyone when she spoke against the motion to immediately start preparing legislation to enable women’s ordination. Betty believed that it was too soon, and that more time was needed for the Church to get used to the idea before risking the divisions that she could foresee if it went too fast.

That same year, Betty was made a Dame of the British Empire, and carried on as energetically as ever, blazing a trail for other women. She had intended to retire in 1980 when she was 70, but stayed on for a further year to allow the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, time to find her successor. And the church had not finished with her even after retirement – a year later, Betty was asked to chair the Crown Appointments Commission to appoint a new Archbishop of York.

Betty ended up retiring to a Hampshire village, and later to a small flat in Winchester. Her energies seemed undiminished and, adding to her long record of being the first woman to hold office in various fields, she was delighted to be elected the first woman on the committee of the Reform Club in London.

Maude Royden

Perhaps most known for her work as a suffragist, Maude Royden was also a preacher, and advocated for women to become priests. In fact, in 1913 she even declared that ‘I go cheerfully as far as women Bishops and Archbishops and Popes’.

Socially aware and devoutly Anglican, Maude’s decision, on finishing her education, to take up work in a slum settlement in Liverpool was not remarkable at that time, but bold for one who had to cope with disability from congenital hip dislocation. She began with high hopes, but the eighteen months she spent in Liverpool left Maude worn-out and disappointed. She therefore reached out to the Reverend Hudson Shaw for advice, who she would have come across whilst studying in Oxford. Revd Shaw, a lecturer and leading figure in the Oxford University extension movement, suggested a change of scene, inviting Maude to help in his Rutland parish.

Revd Shaw found Maude to be articulate and gifted, and despite Oxford having only hired male lectures previously, found her work lecturing on English literature. This was Maude’s start in public speaking, which served her well in the context of women’s suffrage, and later on the issue of women being ordained.

Maude’s feminism stemmed from her Christian faith. However, the Church of England did not seem to share Maude’s position. There were very few clergy members of the Church League for Women’s Suffrage, which Maude helped to found in 1909. But she was sought out by leading Anglicans to address large audiences, especially upon moral questions. For instance, in 1913 the Bishop of Winchester asked her to address 2,000 men at its diocesan church congress.

In 1916, Archbishop Davidson, as part of his national mission to re-Christianise wartime England, asked Maude to speak to congregations across the country. However, he later changed his mind, agreeing with other bishops that women should only speak to their own sex, and only from the foot of the chancel steps. Maude asked at the time whether there were still untouchables, that women should be barred from holy places.

A year later, Maude was offered a preaching post at City Temple, the great Congregational church in Holborn. Three fruitful years in the pulpit of the City Temple confirmed to Maude that preaching was her vocation.

By the time of the 1919 Lambeth Conference, some of Maude’s friends thought it likely she would become the first woman priest, as the Conference would be considering the ministry of women. But the end result was a recommendation that women be allowed to ‘speak’ in church, and even that was hobbled by the old restrictions.

A few years later, Maude established the Guildhouse, an ecumenical place of worship, as well as social and cultural centre in London. Here, Maude preached at the Sunday evening service, and was in such demand to speak that, home or abroad, she was often billed as ‘world famous woman preacher’. She ended up preaching across the globe, though the Guildhouse suffered from her absences, closing in 1936.

During the 1930s, Maude supported the efforts to extend the Anglican ministry of women. She contributed to ‘Frustrated Vocation’, a campaign of letters by women who had felt called to the priesthood. She revealed here how, under present circumstances, denying a woman to take part in the ministry of the Church made it impossible for a sense of vocation to arise.

In 1944, Maude’s “heart leapt with joy” when Miss Li Tim Oi was deaconed in Hong Kong. She later wrote to Li Tim Oi when, under pressure from the bishops in China, she was made to resign, asking how it was possible to ‘resign’ from being ordained.

It would take more than half a century for women in England would be ordained, and not until the month marking the 50th anniversary of Maude’s death that the General Synod would vote that women bishops were “consonant with the faith of the Church”. However, it was through women such as Maude that we’re able to celebrate the progression of the Church, and the vocation opportunities now open to women.

Dame Christian Howard

Christian Howard was a lay leader in the Church of England, whose speaking and writings led many people to debate the traditional exclusion of women from ordained ministry. She had a huge knowledge of the Church of England, as well as the workings of General Synod, while her aristocratic self-confidence helped convince the good and great that female clergy were a respectable cause. Christian strongly believed that women had gifts to offer the Church which should be accepted for the sake of the Gospel and not rejected on anti-feminist grounds.

Born in 1916, Christian grew up in Castle Howard, and was educated primarily at home. However, during the late 1930s, Christian chose to study for the London University certificate of religious knowledge, obtaining the certificate in 1939. Then, in 1943, she gained a Lambeth Diploma in Theology and for two years taught Divinity at Chichester High School.

From 1947 to 1979, Christian held the post of secretary of the York Diocesan Board of Women’s Work. This involved pastoral work and training, and membership of other diocesan committees. Christian felt that those with wealth and privilege should give back in return, demonstrating this belief through her role as a lay representative for the Diocese of York, first on the Church Assembly from 1960-1970, and then on General Synod, of which she was a member from 1970 to 1985. As an elected representative, Christian played an important part in the decision-making of the Church of England, frequently making a decisive late intervention during sessions.

Alongside her various posts on boards and committees, arguably Christian’s key role, in terms of moving towards women’s ordination, was that of research. Christian understood that the road to women’s ordination required thorough scholarly research. She was asked to research the place of women within different cultures and overseas developments in ministry, writing three major reports on the ordination of women, published in 1972, 1978 and 1984. In total, these reports were nearly 300 pages long.

For Christian, women’s search for justice in the church was just as important as remaining alongside the key decision makers, and she did her best to keep different views in harness together. She therefore tried to appeal to traditionalists – in her first report of 1972, the opening paragraph read:

In asking: ‘Can a woman be ordained to the priesthood?’ we are dealing not with a woman’s question, but a church question. Our answer must be determined not primarily by what is good for women, but what is good for the Church. And consequently, ‘What is the will of God?’ ‘What will further the Gospel?’

In 1979, Christian became a founding Vice-Moderator for the newly formed Movement for the Ordination of Women. This organisation was encouraged by Christian’s actions as well as her words – she invited a woman priest from overseas to celebrate in the private chapel of Castle Howard. In this she was convinced she was not overstepping Canon Law. She devoted her chief energies to synodical action, frequently saying “I am a political animal”.

It was through such energies and determination that the Church came to a final decision on 11 November 1992, when the Synod, by a two-thirds majority, agreed to the ordination of women as priests, and then ordained them as priests for the first time in 1994.

Other Resources

- Women and the Church

- A Woman’s Place is in the House of Bishops – Video of an Online Presentation given by Grace Heaton

- The Li Tim-Oi Foundation

- International Anglican Women’s Network

- Archive of the Movement for the Ordination of Women

- “A Woman’s Place…?” – A Story About the Campaign for Women’s Ordination in the Church of England